Asthma in Detail

Asthma: Anatomy and Physiology related to Buteyko Institute Method.

What happens during an asthma attack?

Asthma is an affliction that discriminates against no one. ‘Modern living’ and our reactions to changes in the environment, diet and exposure to infections are just some of the many things that have an effect on asthma. As seen in a recent New Zealand study, up to one third of asthmatic children whose symptoms had disappeared by the age of 18, developed renewed symptoms by the age of 26 showing that asthma can be “grown out of” and return many years later and develop when young or old. Globally, the number of asthmatics has doubled over the past 25 years, in the Southern Hemisphere it’s known that one-quarter of the population of our children suffers from the condition, so it could be said that asthma has well and truly put its roots down worldwide. The strain of this Reversible Obstructive Airway Disorder (R.O.A.D) on our National Health System is reported conservatively at $800,000,000 per year, and with rising death tolls worldwide this human and economic burden has been deemed (by the World Health Organisation) an epidemic with severe consequences.

Derived from the Greek word aazein, “Asthma” means “to breathe with an open mouth”, literally to pant, and this simple definition gives us a generous clue to understanding the link between hyperventilation and asthma. When under attack, asthmatics can feel as though there isn’t enough air or that it is hard to breathe out and as they try to breathe more the attack worsens. So what is really going on here?

To fully understand what happens during an asthma attack, we must first grasp the role of the mast cell in the pathophysiology of asthma. Found in connective tissue, and master regulators of the immune and neuroimmune systems, mast cells are a type of histamine and heparin releasing white blood cell. They play a key role in the inflammatory process, helping with wound healing, immune tolerance and defense against pathogens. Though their protective role in the body is significant, recent research has shown that if mast cells become aggressive they can damage our natural biologic balance. New insights have presented a growing list of diseases and disorders containing mast cell involvement and at the top of the list is asthma.

When comparing mast cell numbers in the bronchial mucosa of those with and without asthma, there does not generally seem to be any increase in the subjects with asthma, though there is evidence that the mast cells localise to 3 key sites: the airway smooth muscle (ASM), the airway mucous glands, and the bronchial epithelium.

Fig 1

An electron micrograph of an activated mast cell in the airway mucosa of a subject with asthma. Magnification ×6000. Picture courtesy of Dr Susan Wilson.

For asthmatics, exposure to allergens that enter the lungs induces IgE- (antibodies produced by the immune system) mediated mast cell degranulation. Inflammatory cells infiltrate the airway wall through chemical mediators that are released during this process, the response is a potent catalyst for the pathologic changes seen in asthma, for example: bronchospasm, mucosal edema, airway hyperreactivity, and mucus secretion. Unfortunately, allergens are not the sole trigger responsible for activating an asthma attack, many other factors may include: Exercise, Illness, Barometric pressure, Household sprays, Seasonal changes and Emotions such as excitement, stress or anxiety. Not everyone suffers from the same triggers, and these triggers may also change within the same person from day-to-day, year-to-year.

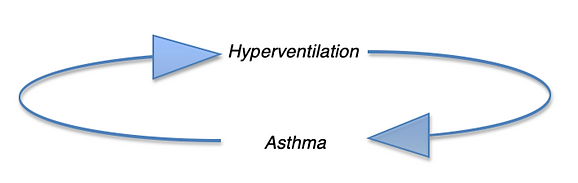

Though hyperventilation is recognised by conventional medicine as the response to the tightening of the airways during an attack, not much attention has been paid to the breathing patterns happening before the trigger sets symptoms off and this is where Buteyko teachers tend to focus their therapy. In the dysfunctional breathing patterns that lead to an attack, perpetuating this viscous cycle.

Fig 2

The cycle of Hyperventilation and Asthma

Physiologically, an asthma attack is due to a narrowing and blocking of the air passageways thus affecting the ability of a person to breathe normally. Hyperventilation that precipitates the attack can cause increased mucous production, clogging the air tubes that mucous would normally lubricate, allowing the air to flow smoothly through, and inflammation and swelling of the lining causing the muscles surrounding the tubes to constrict. This defence mechanism is the body’s way of guarding against loss of carbon dioxide (Co2 is necessary for balancing the blood pH, control of balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, regulation of the breathing pattern, helping to supply O2 to tissues, maintaining steady internal core temperature) and protecting the airways from irritants that may cause harm. The body creates most of the amount of this precious carbon dioxide gas that we need and when CO2 tension is low, mast cells release even more histamine further narrowing the airways and thickening mucous. The size of the opening of the air tube is controlled by muscle reflex and guided by the part of the nervous system that controls involuntary reflexes like blinking. Because of this automatic response we have little conscious control over these muscles and we all have the potential for constriction of airways in response to irritants. However, the airways of asthma patients could be described as over-reactive.

Fig 3

The physiology of a normal airway and asthmatic airway during an attack. Illustration courtesy of Ophea Asthma Friendly website (CA)

Fig 4

Mucous Plugs.

Knowing now that Asthma has been related to dysfunctional breathing and hyperventilation we can look at how the Buteyko Retraining Method (BM) has effected the resting ventilation in asthma patients. Published in the European Respiratory Journal (Sept 2015), was a 6 months trial conducted with 18 asthma patients with 3 separate evaluations, the first being a control period where no BM was applied. Patients’ Ventilation (V'E), CO2 output (V'CO2), partial end-tidal pressure of CO2 (PETCO2) and O2 (PETO2) were measured at rest and during the control period and none of the measured parameters changed, though after BM the results were significant: PETCO2 increased from 33.4±3.9 to 35.4±2.7 mmHg (p<0.01), PETO2 decreased from 107± 5 to 103± 4 mmHg (p<0.01), BHT increased from 13±7 to 25±10 seconds (p<0.0001), ACT increased from 16.5±5.0 to 21.4±3.3 points (p<0.005), FEV1/FVC remained 0.74 (NS) and V'A/VCO2 remained 38.6±7.8 (NS). There were no changes in the control group. In this study there is a clear conclusion that BM improved asthma control by increasing the partial end-tidal pressure of CO2 (PETCO2), offering a reduction of the respiratory center sensitivity.

It is essential for our body to maintain a normal arterial blood pH of between 7.35 and 7.45 and our survival instinct makes sure of this, so how does breathing and carbon dioxide fit into this equation? CO2 is a major factor in keeping these levels regulated and as asthmatics typically have a lower CO2 level, due to chronic over breathing, when ‘triggered’ the body stresses and breathing increases even more.

CO2 is a weak acid it can combine readily with water to form carbonic acid, breaking down even further into bicarbonate ions if blood acidity is too high, attempting to increase alkalinity. It is easily maintained or removed by the automatic altering of our breath, so this proves to be a vital way to make sure that our pH levels stay healthy, and if levels are unable to be regulated by breathing the kidneys will take over in this process of compensation. Perhaps one of the most well known published explanations of the capabilities’ of carbon dioxide is by the early 20th century Danish scientist Christian Bohr, his discovery is known as ‘The Bohr Effect’.

Based on scientific fact, The Bohr Effect reveals to us that the reality of what is happening inside our body does not in fact correspond with how we may feel when we breathe a certain way. Paradoxically, when we breathe deeply and more air than is needed is delivered, our tissues cells actually become starved of oxygen. The same is true when taking in too little air as this creates insufficient oxygen in the bloodstream; again the result is less oxygen in tissues. The Bohr effect is a phenomenon that simply states, “Haemoglobin's oxygen binding affinity is inversely related both to acidity and to the concentration of carbon dioxide”.

Haemoglobin molecules are constantly releasing oxygen therefore they cannot ever be 100% saturated, so it is not possible to improve the collection of O2 by Haemoglobin, which one might think they are doing when increasing their breathing volume. One molecule carries a maximum of 4 oxygen molecules, their bond is as tight as can be, only releasing when the conditions are ideal i.e.: dependent on the production of carbon dioxide.

If, during an asthma attack, airways constrict and carbon dioxide levels plummet, Respiratory Alkalosis can occur, haemoglobin then becomes viscous and unable to release its oxygen to the tissues, this means that now even less carbon dioxide is produced. Through this process we can see how easily The Bohr effect can send an asthmatic spiralling down and into a vicious cycle of decreasing CO2 levels and lack of oxygen release. With particularly severe asthma, (Status asthmaticas) there may come a point where the bloodstream cannot gain sufficient oxygen and carbon dioxide cannot get out. The gases literally cannot exchange due to the plugging of mucous and as the lungs are cut off from ventilation sections will collapse.

Fig 5

Oxygen binding by dog blood (solid lines) and horse blood (dashed line) as a function of O2 partial pressure at different partial pressure of CO2. The shift to the right is caused by The Bohr effect; a decrease in blood pH or an increase in blood CO2 concentration will result in haemoglobin proteins releasing their loads of oxygen. .

So how can we formulate therapy through understanding these events?

Buteyko training is essentially a non-invasive ventilation treatment for asthma suffers, increasing carbon dioxide levels to normal and reducing the chronic and unconscious over breathing that always precipitates an attack. Many studies have reported that, on average, asthmatics are breathing 2-3 times the volume of air per minute (up to 14 litres) than those without asthma (4-6 litres) and generally through their mouths instead of noses (as well as having a predisposition to the asthma gene). Through awareness of The BOHR effect we know how critical carbon dioxide is and for many regulatory processes in the body. Using a bronchodilator during an attack is an effective way to quickly open the airways and prevent further CO2 loss though relief may be temporary as medications do wear off and can also unfortunately precipitate further attacks by allowing more over breathing and CO2 loss through newly opened airways. Yet another disturbing and dangerous cycle. While Buteyko practitioners do not in any way advise on medication reductions or change, most asthmatics that practice the BM technique find that as their CO2 levels rise and breathing normalises, symptoms tend to disappear on their own, as does the need for any medications.

REFERENCE LIST

Stark, J., and Stark, R. (2002). The Carbon Dioxide Syndrome. QLD, Australia: Buteyko Works Ltd.

Duben-Engelkirk, P. G. (2011). Burton's Microbiology for the Health Sciences - Ninth Edition. Baltimore, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Marieb, E. N. (2012). Essentials of Human Anatomy & Physiology - Ten Edition. San Francisco , CA, USA: Pearson Education.

Brewer, D. S. (2009). Overcoming Asthma, the complete complementary health program. london: Duncan Baird Publishers.

White, G. (n.d.). Clinical Trials. Retrieved from Buteyko Breathing Clinics: http://www.buteykobreathing.nz/page/194565

The good, the bad & the ugly. Retrieved from Mast Cell Aware: http://www.mastcellaware.com/mast-cells/about-mast-cells.html

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Mast Cell. Retrieved from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mast_cell

Bohr; Hasselbalch, Krogh. Concerning a Biologically Important Relationship - The Influence of the Carbon Dioxide Content of Blood on its Oxygen Binding.

Asthma & Allergies. (n.d.). Retrieved from Breathe On: http://www.breatheon.com/asthma-and-allergies/

Asthma Australia. (n.d.). Asthma Australia. Retrieved from What is Asthma: http://www.asthmaaustralia.org.au/national/about-asthma/what-is-asthma

Asthma Ventilation Stratergies. (n.d.). Retrieved from Dont forget the bubbles: http://dontforgetthebubbles.com/asthma-ventilation-strategies/

Immunology, T. J. (n.d.). Images in the role of the mast cell in the pathophysiology of asthma. Retrieved from The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: http://www.jacionline.org/action/showFullTextImages?pii=S0091-6749%2806%2900514-8

ASTHMA ATTACK-LEARN ABOUT WHAT HAPPENS WHEN IT OCCURS. Retrieved from What Asthma Is: http://whatasthmais.com/asthma-attack-learn-about-what-happens-when-it-occurs/

Journal, E. R. (n.d.). Effect of Buteyko breathing retraining method on resting ventilation and asthma control in asthma patients. Retrieved from ERS: http://erj.ersjournals.com/content/46/suppl_59/PA2282

Organization, World. Health. (n.d.). Bronchila Asthma. Retrieved from WHO: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs206/en/

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Pathophysiology of Asthma. Retrieved from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pathophysiology_of_asthma